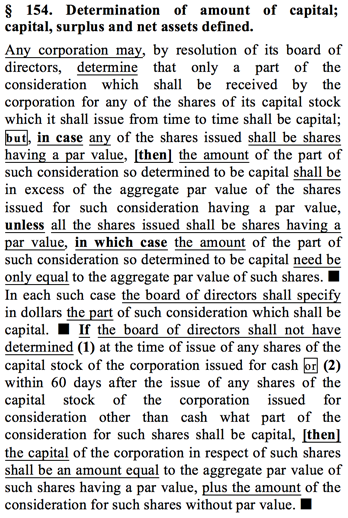

Statutory sentence structures are often complex. Visilaw is a system for marking statutes that is designed to make them easier to read and analyze.

The markings provide at least six benefits.

(1) They promote analysis by visually dividing complex sentences into clauses that can be read and analyzed one-at-a-time.

(2) The highlighting of skeletal sentence structure within each clause facilitates scanning, speeds reading, and improves comprehension.

(3) The markings improve interpretation by indicating the grammatical structure of each sentence.

(4) The markings make reading easier and reduce reader stress by identifying cohesive phrases that can be treated as single units.

(5) Highlights make it easy to find the conjunctions that indicate the relationships among listed items and subparagraphs.

(6) The markings signal the relationships among clauses and phrases.

The markings are sufficiently intuitive that most readers will benefit even without prior instruction or practice. With instruction, practice, and experimentation, the markings can provide much greater benefits. I encourage you to think of them as a set of tools, the full power and scope of which differ from person to person. The remainder of this introduction explains what each of the markings means and provides suggestions on how to use them.

1. Sentences. Sentences are the fundamental building blocks of statutory material. Each can be analyzed separately. To analyze one, it is helpful to know where it begins and ends. Knowing can be difficult. Sentences often run across the visual boundaries of subsections and the device traditionally used to mark them – the lowly period – is so small as to be nearly invisible. The solution is to add a larger, more easily visible mark if the sentence does not end at the end of a section or subsection.

Example: Sentence Marking

If the end of a sentence is not the end of the section or subsection in which it appears, I have marked the end of the sentence with a solid black box, like this. If a sentence ends at the end of a section or subsection, no marking is necessary and none appears.

How to use sentence-end marks: Note visually where the sentence of interest begins and ends before you try to read it. Ignore surrounding text until you grasp the meaning of the sentence.

2. Primary if-then clauses. Statutes are legislative commands in sentence form. In each sentence, the legislature indicates, expressly or impliedly, that if certain conditions are met, then certain consequences follow. Although not all statutes are structured as if-then statements, if-then structure is natural and common for well-drafted statutory material.

The if-then structure of statutory sentences is often obvious. The sentence begins with the word “if” followed by a clause that specifies conditions (the “if-clause”), and finishes with the word “then” followed by a clause that specifies consequences (the “then-clause”). Typically, each of the clauses contains a subject, a verb, and perhaps a direct object. But for the dependent marker words “if” and “then,” each clause could have been a sentence on its own. Together, the two clauses typically comprise the entire sentence.

Example: Primary If-Then Clause Marking

this sentence were in a statute, I would have marked it like this.

I refer to such an if-then structure as a “primary” structure to distinguish it from secondary structures that appear within independent or dependent clauses. I have marked primary if-then structures by making the “if” and “then” boldface and underlining them.

Primary ifs and thens receive the most prominent marking used within a sentence because they divide the sentence into parts that the reader can analyze separately.

The words “if” and “then” do not appear in every statute that has an if-then structure. First, statute drafters often substitute structurally equivalent words for “if.” Examples include “when,” “while,” “until,” “unless,” “wherever” and “to the extent that.” I have marked those equivalents in the same manner as “if.” Second, drafters often leave the word “then” implied. I made each implied then express, placing it in brackets to indicate that it does not appear in the statute. An implied “then” looks like this: [then].

How to use primary if-then marks: Primary if-then markings enable the reader to see the position of the if-then structure before starting to read. Because each clause is in essence a sentence, the reader can read one and grasp its meaning before reading the other. The reader also can read the clauses in either order, depending on the reader’s interests. By scanning the if clauses in a group of statutes, a reader can determine which of those statutes will apply to his or her case. By scanning the then clauses in group of statutes, a reader can determine which statutes might yield a desired result.

3. Primary conjunctions. Two kinds of conjunctions are primary: sentence dividers and paragraph dividers. A sentence divider separates clauses. By “clause” I mean a dependent or an independent clause that contains the basic elements of a sentence – subject, verb, and perhaps direct object. The clauses separated can be multiple if-clauses (if a and if b then c), multiple then clauses (if a, then b and then c), or multiple independent clauses (a and b). Most primary conjunctions are “and” or “or.”

Example: Primary Conjunction Marking

I have made primary conjunctions boldface, and I have boxed their texts.

In statutes, unlike in prose, a single sentence is often divided into multiple paragraphs. The motivation of the drafters is usually to group together words that should be read together because they comprise one item in a list. Thus if there is a paragraph a, there will be a paragraph b, and perhaps additional paragraphs of the series. In nearly every instance, the paragraphs are alternative requirments only one of which must be met – indicated by “or” between the last two paragraphs – or multiple requirements all of which must be met – indicated by “and” between the last two paragraphs. I refer to these conjunctions as paragraph dividers because, although they usually appear only at the end of the penultimate paragraph in the list, they implicitly appear between each pair of paragraphs in the list. Unfortunately, paragraph dividers seldom appear where statute readers need them – at the end of the first paragraph in the series. Amidst paragraphs and subparagrahs, they can be difficult to find. To make finding them easier, I have highlighted conjunctions that are primary – first level – paragraph dividers in the same manner that I highlighted conjunctions that are sentence dividers.

How to use primary conjunctions: Except when they appear at the end of a paragraph, treat primary conjunctions as sentence subdividers – equal to an “if” or a “then,” but superior to all other dividers. For example, treat the following sentence as divided into three parts (an independent clause, an if-clause, and a then-clause: “Sales of accounts are security interests and if security interests are in default, then they may be foreclosed.”

4. Skeletal sentences. A “skeletal sentence” consists of the subject, verb, and direct object of an independent or dependent clause, along with the articles, adjectives, and adverbs that directly modify the subject, verb, or direct object. I have underlined the words that comprise a skeletal sentence. That marking accomplishes two things. First, it defines a short sentence or independent clause – that is, a complete thought – that, when read, conveys the gist of the entire sentence or clause. Second, it divides that sentence or independent clause into a highlighted core structure and other, un-highlighted words and phrases that modify words in the core structure.

I have highlighted at least one skeletal sentence for nearly every sentence that appears in the statutes. If a sentence is divided into primary if-then clauses, I have marked a skeletal sentence in each if-clause and in each then-clause.

Example: Skeletal Sentence and Primary Conjunction Markings

A security interest in property subject to a statute, regulation, or treaty described in subsection (a) may be perfected only by compliance with those requirements, and a security interest so perfected remains perfected notwithstanding a change in the use or transfer of possession of the collateral.

The primary “and” divides this sentence into two parts. The underlining indicates the gist of each part. The gist of the first is that “a security interest may be perfected.” The gist of the second is that “a security interest so perfected remains perfected.”

How to use skeletal sentences: Begin by noting where the sentence begins and ends. Then look for primary if-then structures and primary conjunctions. If they appear, they divide the sentence into separately-analyzable parts. Each part is a clause with its own subject and verb. The smaller number of underlined words in a part constitute the skeletal sentence for that part. Focus on one such skeletal sentence. Read the skeletal sentence first to understand generally what the sentence does. Then consider how the remaining words of the sentence change its meaning. Keep in mind that the most important words in the sentence may not be in the skeletal sentence. The skeletal sentence underlining indicates structure, not importance.

5. Secondary if-then clauses. If-then structures that do not qualify as primary are secondary. An if-then structure may not qualify as primary because (1) it does not divide the sentence into sub-sentences that can be analyzed in isolation, or (2) the condition relates to only a part of the sentence. Most secondary if-clauses state conditions that, if met, result not in the primary consequence, but in some lesser consequence. I have highlighted secondary if and then clauses by double-underlining the “ifs,” “thens,” and equivalents.

Example: Secondary If-then Marking

UCC § 9-203(b)(3) provides that a security interest is enforceable only if one of the following conditions is met:

(A) the debtor has authenticated a security agreement that provides a description of the collateral and, the security interest covers timber to be cut, a description of the land concerned;

This if-then structure is secondary because the first requirement in subsection (A) – a description of collateral – applies even if the condition is not met. The condition determines only the need for a description of the land.

Independent clauses having both a subject and a verb usually do not exist within secondary if or then clauses. Even when they do, I have not marked them as skeletal sentences to avoid confusion with primary skeletal sentences.

How to use secondary if-then clauses: Locate the “if” and corresponding “then.” Consider each clause separately, but keep in mind that elements of the clause may be implied from and found in, other parts of the sentence. If the condition is met, the condition becomes irrelevant. You can read the sentence as if the conditional language were not present. If the condition is not met, the entire secondary if-then clause becomes irrelevant. You can read the sentence as if the secondary if-then clause were not present.

6. Primary exceptions. A primary exception is an exception that applies to the entire sentence. That is, if the terms of the exception are met, the sentence has no application. I have used prominent parentheses that appear as half-circles to mark the beginning and end of each primary exception. They appear like this.

How to use primary exceptions: Depending on the circumstances that brought the reader to the statute, the reader can either (1) analyze the section, ignoring the exception language until the analysis is complete, or (2) analyze the exception, ignoring the remainder of the exception until the reader determines whether the exception has rendered it irrelevant.

7. Secondary exceptions. A secondary exception is an exception from part of a sentence, but not from the entire sentence. I have indicated the beginning and end of significant secondary exceptions with prominent parentheses that appear as half-diamonds. They look like this.

How to use secondary exceptions: Readers can ignore the secondary exception in analyzing the part of the sentence to which the secondary exception applies, until after the reader has analyzed that part.

8. Cohesive phrases. A cohesive phrase is a group of words that are best read as a single unit. A cohesive phrase may be a term or art, a qualification, the specification of an amount, or the specification of a hypothetical (to name just a few possibilities). Sometimes it may be helpful to think of the entire phrase as a multi-word noun. The phrase may be two or three words, or it may continue for several lines of text. I used bold parentheses to mark the beginning and end of each cohesive phrase.

Example: Cohesive Phrases

[T]he term “contractual right” includes a right set forth in a rule or bylaw of . . . a securities clearing agency, a contract market designated under the Commodity Exchange Act, a derivatives transaction execution facility registered under the Commodity Exchange Act, or a board of trade (as defined in the Commodity Exchange Act), or in a resolution of the governing board thereof,

As in the above example, cohesive phrases are often items in a list. When they are, each item is likely to start with the same word and a conjunction indicating the relationship among them will appear between the last two items. When cohesive phrases are used as terms of art, they tend to repeat in the same sentence or in nearby sentences.

Cohesive phrases may be nested one within another. Each may have its own complex structure within it. To maintain simplicity in the marking system, I marked only a single level of those cohesive phrases. That is, the cohesive phrases I marked do not overlap and are not nested. Nor do they overlap with skeletal sentences. They are always in peripheral parts of the sentence.

How to use cohesive phrases: Read cohesive phrases from the inside out. That is, begin by reading and understanding the phrase as a unit. Then consider that unit in the context of the sentence. If the cohesive phrase is a modifier, try to determine what it modifies. If cohesive phrases appear in a list, examine the context to determine the consequence or significance of appearing on the list. Scan surrounding sentences to see if the same cohesive phrase appears in them.

9. Secondary conjunctions. A conjunction is secondary if it indicates an important relationship, but does not qualify as a primary conjunction. (Most conjunctions qualify as neither primary nor secondary.) Secondary conjunctions appear in a smaller font and in text boxes.

I have used secondary conjunction marks in three ways. First, in skeletal sentences, they indicate the relationship between multiple subjects, verbs, or direct objects. Second, in lists composed of cohesive phrases, they indicate the relationship among the cohesive phrases. Third, where I have marked primary conjunctions to indicate the relationships among subparagraphs, I have marked secondary conjunctions to indicate the relationships among sub-subparagraphs.

Example: Secondary Conjunction

Secondary conjunctions appear in a smaller, not bolded font and in text boxes.

How to use secondary conjunctions: Read secondary conjunctions that appear within the bounds of a skeletal sentence as part of the skeletal sentence (unless the context otherwise requires). Read secondary conjunctions that appear between cohesive phrases as indicating the relationship between the cohesive phrases. The “and” in the phrase “a and b” exemplifies this circumstance. When seeking to determine the relationship among items listed in sub-subparagraphs, look for the secondary conjunction at the end of the penultimate item in the list.

If the cohesive phrases are lengthy and more than two appear in the same list, in rare instances I replicated the conjunction between each pair of listed items. Of course, I put the conjunction in brackets to indicate its addition. To illustrate, if the sentence contained the structure “a, b, and c” and the second cohesive phrase was lengthy, I might render it “a and b, and c.”

10. Custom markings. Readers may find it useful to add their own markings to VisiLaw® text. The most common reason for doing to is to indicate importance. Because my markings are in black, readers need only use color for their markings to be easily distinguishable.

Suggestions for custom markings. Readers may wish to highlight words that are not included in the skeletal sentence, but that are crucial to the meaning of the sentence. Readers seeking to apply a statutory provision to a real or hypothetical case may wish to highlight the particular words that apply. A red or blue pen will do that nicely.